Romeo Fratti

Introducing this issue dealing with cultural and ethnic tensions between Italian and Chinese communities, historian Philip F. Napoli gives a first pragmatic approach in his essay Little Italy: Resisting the Asian invasion, 1965-1995: according to Napoli, Manhattan’s Little Italy is many things at present, but it is not an ethnic Italian community[1]. It goes without saying that as an urban ethnic enclave Manhattan Little Italy has indeed vanished, in the path of an expanding Chinatown. But this urban and sociologic passage did not come without effort to try to keep an Italian identity.

In the sixties, Italians and Chinese coexisted side by side along Canal Street, which worked as an informal barrier between both enclaves. But since 1965 Chinatown started extending its territory to north of Canal Street, Italian-Americans’ fear of being squeezed out rose and they began expressing a need to preserve the exclusive ethnic character of their borough, which for several decades had represented – to repeat what chairman of the New York Planning Commission Victor Marrero said – a home-away-from-home: To many New Yorkers, Little Italy is a home-away-from-home. To thousands of visitors from miles around, it is a place to sample special flavors… It is a magnetic regional asset and one of the City’s most vital neighborhoods. Shaped by generations of New Yorkers, it is a critical part of our urban heritage.[2]

The Italian-American reaction can be most easily identified by the organizations launched in the sixties and the seventies to claim for some measures of cultural and political recognition of the Italian footprint. The Congress of Italian-American organizations, founded in 1965, focused on issues linked to the social services needs of Italian Americans. The American-Italian Historical Association was founded in 1966 and declared in its articles of incorporation to be concentrated on the collection, preservation, development and popularization[3] of materials related to the Italian-American experience in the United States and in Canada. The Italian-American Civil Rights League was created in 1970 and was devoted to stamp out discrimination against Italian-Americans; it was particularly focused on negative media portrayals of the community. The Italian-American Coalition, also founded in 1970, was comprised of 25 fraternal, civic, labor, professional and social organizations, which also tackled discrimination against Italian-Americans. But we should examine the crucial role played by a certain association in order to give Little Italy a new boost.

The pivotal role of LIRA in building today’s Little Italy

Aiming to solve both the decline of the area and the expansion of Chinatown, some associations composed of Little Italy residents were formed to keep an “Italian spirit” in the heart of Manhattan. To give the most meaningful example, in early 1974 the Little Italy Restoration Association (LIRA) was inaugurated. Its aim was clearly to trigger a cultural reaction against the risk of Little Italy dilution. One of LIRA’s first ideas involved the implementation of San Gennaro feast in Little Italy – a key point we will insist on in the second part – to help the revival of an Italian-American community gathering: we ought to bear in mind that San Gennaro feast is still today one of Little Italy’s largest sources of interest and income.

The association was first and foremost oriented towards fighting against the growing infiltration of other nationalities[4]. Its plan for restoration was meant for attacking the neighborhood’s growing decay and the perceived loss of ethnic population[5].

In February 1977, with the support of the New York Planning Commission, LIRA launched a “Risorgimento”[6] Plan to revitalize the core of Little Italy. The purpose of this plan was to identify, preserve and enhance the enclave’s special qualities, so it can remain vital and viable.[7] The plan included – amongst others initiatives – the designation of a Little Italy Special District and several proposals to revitalize Mulberry Street. In the wake of LIRA’s “Risorgimento” Plan, the New York Planning Commission produced a document which set up the premises for the future development of the district. This document put forward seven key points focusing on the specific protective goal of the area’s Italian identity. The targets of the document included the preservation of the character of the community, the emphasizing of the commercial character of the whole area, the focus on pedestrian traffic, the rehabilitation of existing buildings and the providing of green spaces.[8]

Regarding administrative division, it was the New York Planning Commission that officially denominated the Italian-American neighborhood as “Little Italy”. As is shown on the map[9] below, the Commission additionally traced Little Italy Special District official boundaries for the area, but it did so while completely disregarding the demographic composition of the community:

The Little Italy Special District therefore consisted of the area between Canal Street to the south, the Bowery to the east, Bleecker Street to the north and Baxter, Center and Lafayette Streets to the west. From then onwards, the district included four sections: The Houston Street Corridor, The Bowery, Canal and Kenmare Corridor, and The Mulberry Street Regional Spine, itself part of the larger Preservation Area.

But above all, LIRA and the Commission concentrated upon preserving the Little Italy cultural and commercial core, situated in the already mentioned portion of Mulberry Street between Canal and Broome Streets. The plan concentrated on “designing” a street atmosphere, charged with Italian ethnic identity. The preservation efforts began to yield results soon after the publicizing of the “Risorgimento” Plan: between 1975 and 1981, 15 new restaurants opened on Mulberry Street, while others were renovated.[10] However, as we will see in the following strands of analysis, these initiatives didn’t manage to slow down an irreversible process.

Little Italy and Chinatown: A requisite cooperation?

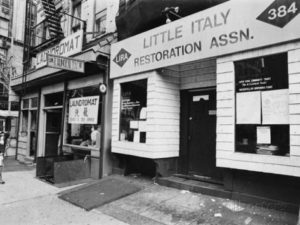

In order to examine what we aim to discuss soon, if we look at this 1970s photograph below[11] we will notice that, ironically, a Chinese Laundromat is exactly next door to the offices of the LIRA. This photograph alone shows the limits of the battle against cross-fertilization.

In 2009, as a result of this unavoidable Chinese-Italian cross-fertilization and due to the mixing of both boroughs, Little Italy and Chinatown were listed in a single historic district on the National Register of Historic Places. This decision is the achievement of a several-year work led by the “Two Bridges Neighborhood Council”. Since the fifties, this association has been fighting to preserve and promote the heritage worth as well as the cultural memory of both Little Italy and Chinatown[12]. Amongst the overarching arguments endorsing this valorization project was the coexistence of two ethnic communities that had been living in close proximity since the end of the 19th century. On the other hand, the “Two Bridges Neighborhood Council” wished to point out that these two urban enclaves were ranked among the most populated immigrant communities in New York and had actively participated to the New Yorker immigration history: Chinese-American and Italian-American ethnic heritage and social history, particularly in association with the history of immigration in America.[13]

In 2010, in order to celebrate the two boroughs federal registration, a cultural events day called East meets West was organized. It was located on what is still today considered as the borderline between Little Italy and Chinatown: on that day, a small parade performed Marco Polo travelling in China, as the symbol of a first meeting between two different worlds that had to be inclusive and cooperative, even within the framework of an urban area. Pictured below[14] is the panel of the East meets West 2nd edition, which took place in 2011. East meets West attracts hundreds of people, essentially tourists and “suburban Saturday Italians”[15]. But does this manner of collaborating from a cultural standpoint reflect an economic cooperation?

In the present day, remnants of old ethnic tensions still exist. Anthony Luna, owner of Luna restaurant on 115, Mulberry Street told the New York Times – in an article reported by Philip F. Napoli – that a Chinese buyer had made him a several million dollar offer on property he owned in the area, but he decided to sell it to someone he knew instead. We stick together, he said. We Italians don’t want to sell anymore to the Chinese. We want to keep it Little Italy.[16] Anne Compoccia, leader of the Little Italy Chamber of Commerce, insists that Little Italy’s old charm and its inhabitants’ determination to stay put, will enable this borough-turned-tourist-attraction to survive. We’re stemming the tide, she says. Even if it’s down to just ten blocks, we’re going to preserve it.[17]

_____________________________________________

[1] Philip F. Napoli’s essay, quoted by Jerome Krase in Seeing Cities Change: Local Culture and Class, Op. cit., p. 76.

[2] Victor Marrero, Chairman of the New York Planning Commission, quoted by Bernard Debarbieux in « Comment être « italien » à Little Italy? », Via@ – Revue internationale interdisciplinaire de tourisme, 16 mars 2012, p. 13.

[3] Philip F. Napoli, Op. cit., p. 20.

[4] Goals being set by the LIRA, quoted by Bogdana Simina Frunza, Op. cit., p. 27.

[5] Ibidem, p. 28.

[6] “Risorgimento” means “revival” in Italian.

[7] Goal being set by the “Risorgimento” plan, Ibidem, p. 28.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] Little Italy Special District Plan, disclosed by Bogdana Simina Frunza, Ibidem, p. 30.

[10] Ibidem, p. 29.

[11] Picture taken from the website www.allposters.com: http://www.allposters.com/-sp/A-Chinese-Laundromat-is-Seen-Next-Door-to-the-Offices-of-the-Little-Italy-Restoration-Association-Posters_i4060787_.htm

[12] Bernard Debarbieux, Op. cit., p. 8.

[13] Ibidem, p. 9.

[14] Picture taken from the website www.hellohailey.com: http://www.hellohailey.com/portfolio/east-meets-west-parade-poster/

[15] Sam Roberts, Op. cit.

[16] Philip F. Napoli, Op. cit., p. 29.

[17] Ibidem.