Jeremy Lester

... the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood. Susan Sontag

It is just possible that photography is the prophecy of a human memory yet to be socially and politically achieved. John Berger

* * * * *

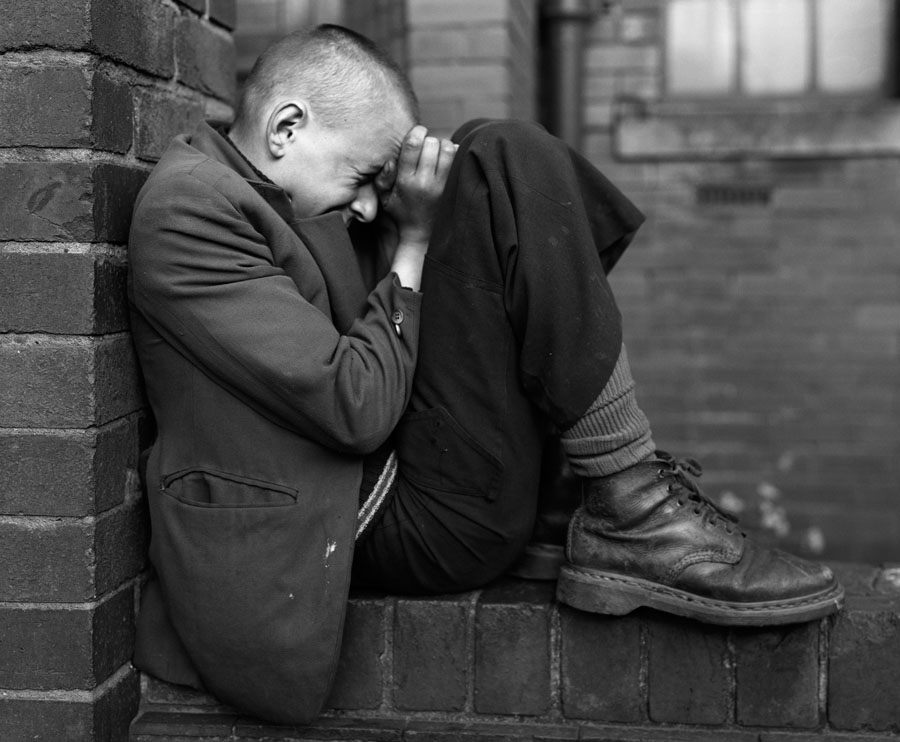

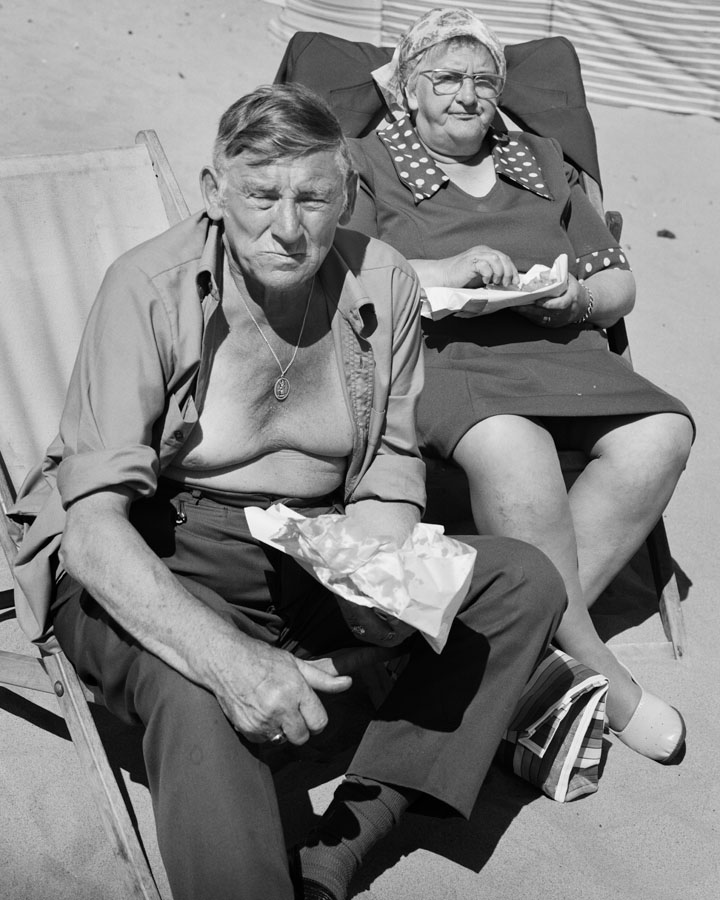

The power of a photograph always lies in its capacity to remind us of something. For a photograph to do this, it is not important whether we ourselves took it, whether we appear in it, or indeed whether it has anything directly to do with us. It is enough that it touches us in some way. Its stillness triggers empathy. It allows the mind to wander and as the mind slowly drifts away from the present we re-live, albeit perhaps only fleetingly, thoughts and images from the past, our own past. This is exactly what these photographs of Chris Killip did. They stirred personal childhood memories – memories of economic hardship (if not outright poverty), pain, and anguish; of grim, bleak, alienating landscapes; and of the drudgery and burden of everyday existence. The images are harsh and stark; they are never sentimentalised. But at the same time, if there is misery here, it is never humiliating. As a consequence, there are also memories of hope, of tremendous dignity, of pride, and of the small pleasures that sustain life. Last but not least, and let us be honest here, there are the memories of the burning desire to escape, but also of the sense of loss that followed in the wake of this exodus; perhaps one might even say, this ‘running away’.

When he takes a photo of someone, Killip has that rare ability to capture more than an instant in time; what he is really able to capture is the essence of an individual’s whole life. They tell us almost everything that we need, or that we would want, to know about them. We can read their life story in the photographic image. It is for this reason that the people in the photographs are not strangers to us. It is as if we know them, we are familiar with them.

_________________________________________________________________________

*Chris Killip (born 1946) Is an English photographer of international renown whose work has always tried to document key aspects of the political and social life of working-class communities (past and present). His photographs are featured in the permanent collections of major institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; Museum Folkwang, Essen; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and most recently, Tate Britain in London (as well as many others). He has also been the winner of many prestigious prizes, such as the 1989 Cartier- Bresson award for his work In Flagrante. More recently he has also turned his attention to non-fiction short films, and one such film, Skinningrove, was awarded the prize of best film in its category at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival. The following short tribute and analysis is based on a viewing of his recent exhibition entitled What Happened: Great Britain 1970 – 1990, which was shown at Le Bal Gallery in Paris, together with another exhibition (entitled Arbeit/Work) held last year at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid. All the photographs reproduced here are done so with the very kind and generous permission of the photographer himself.

He has been called the chronicler of a bygone era; the last photographer of the working class. Both descriptions are only partly true. One appreciates the specific time and locality of what he is showing us – the old industrial landscape of northern England in the 1970s and 1980s – and one fully understands how this has been destroyed and decimated, along with the livelihoods they once supported. But one should not imprison these images in just one time and space. Like the work and the factories that once sustained them, they are movable images, re-locatable in space and time. Indeed, in many ways, a lot of his photographs, particularly those depicting redundancy and unemployment (as well resistance to these phenomena) may well be considered not a last image of a vanishing world, but instead a first glimpse, portent, or forewarning of the contemporary world that we now live in, which is dominated so much by the conditions of precariousness. The industrial working class has just about completely vanished, but the global and far more universal ‘precariat class’ looks as though it is going to be with us for a long time to come (unless we can find the will and means to resist).

***

I want to focus on three photographs in particular, each one of which gives us an image of exactly the same location, always taken from the same position. It is a street in Wallsend (on Tyneside) located right next to the Swan Hunter shipyard, which was the work that sustained the region for many decades stretching back in time. No more than six years separate the images in real time – the first one in 1975 and the last one in 1981 – but an eternity separates their meaning and significance.

In the first one, we see a scene that would have been a typical one at any time during the existence of the shipyard. There are children playing in the street, but no adults to be seen. The men are busy at work; the women are busy with their own daily chores. The children play quietly, tranquilly, together. This is still an age when the street was the natural playground for the child. They have nothing to sustain their amusement and their enjoyment other than the power of their own company and imagination. One of the children is temporarily distracted from what he had been doing. He has seen the photographer and he is looking directly in his direction. Strangers or casual visitors from outside would have been quite rare so it is natural that the boy is curious. But one suspects that it was only a momentary distraction. He would not have been unnerved, let alone frightened, by the stranger. He would have accepted him, let him get on with whatever he was doing, and he himself would have immediately picked up the threads of the game or the conversation with his fellow children (one of whom, I am pretty sure, would have been his sister).

To the left of the children (as we look at the picture) are the houses where they, their parents, their other relatives (near and distant), and the other shipyard families live. They are small tenement houses that are situated in neat, identical rows with no space separating them in the row that they belong to. They are houses that would have been owned either directly by the shipyard, or, more likely at this time, by the local council, with the rent due on the same day each month (and how one used to dread that day).

The Russian writer, Evgeny Zamyatin, who lived and worked in this region for nearly two years during the First World War – he helped design and build icebreakers, one of which was later re-named “Lenin” following the death of the first Soviet revolutionary leader – had an absolute hatred of these houses. In letters that he wrote home to his wife, he likens them to the storehouses and grain barns in Petersburg near the Aleksandr Nevskii monastery, and he cannot believe that people actually live in them. Above all, he is shocked and depressed by the fact that each one is an absolutely identical cardboard cut-out of the others to the same, dull, depressing zero degree. It is as though the people live surrounded by mirrors, with each house being an exact reflection of the others. ‘What a terrible lack of imagination’, he repeatedly wrote; what lack of spontaneity, what conformism they convey.(1) In his short story, ‘Islanders’, which he wrote during his stay on Tyneside, he wonders how the parishioners when they leave the church on Sunday can possibly re-locate their own houses, and the fact that somehow they can is likened to a veritable ‘miracle’. Is it any wonder, his narrator goes on to reflect, that the English are so herd-like, so set in their ways, and that any kind of originality is considered almost ‘criminal’. So deep were his negative impressions that he experienced here that they would later be used as a direct source for the physical contours and setting for his most well-known, nightmarish dystopian novel – We.

Of course, one understands his perspective, but it was the perspective of an outsider. For the people actually living here, the closeness and the identicalness of the surroundings would have been the bedrock of their shared sense of community. As always, what we read into an image or a landscape is dependent upon perspective and upon the subjective eye of the beholder.

To the right of the children playing in the street a wall extends into the distance as far as the eye can see. It is a boundary that theoretically separates the realm of the workplace and labour from the realm of the home and leisure. But so low is the wall, so tenuous is the separation, one knows full well that the one conjoined directly with the other. There was no real separation at all.

Towering above the children are the cranes of the shipyard. In their tentacles lies the product of the collective work performed by thousands of blue and white collar workers stretching over many years. At the time the photograph was taken the ship that can be seen was the biggest one ever built on the river estuary. “Tyne Pride” is its name (as we can just make out from the photograph), and for sure it bore the pride of those who made it. But what a price was paid for this pride. Few industries could have contributed more to the power of English imperialism than that of shipbuilding, for what would the might of English power have been without its capacity to rule the high seas of the world? But at the same time, few workers in any industry suffered more toil, exploitation, sickness, injury and death than shipworkers. Moreover, as the industry became ever more ‘modernised’ so too did the illnesses. Only later – when it was too late – would it be revealed the extent to which the workers were poisoned by their constant exposure to asbestos.

It surely does not take much imagination to begin to see the ship as some kind of monster. Indeed, both the children and the houses as well are living so cheek by jowl with this monster that its jaws could seemingly devour them at any moment. One is inevitably reminded here of Melville’s description of the great monster whale, ‘Moby Dick’ – its sweeping ‘sickle-shaped jaw’ which can tear human flesh as a mower can shear a blade of grass in the field. How it must often have been seen as the incarnation of malicious torments that demonise those who come into direct contact with it.

All that most maddens and torments; all that stirs up the lees of things; all truth with malice in it; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil… were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick.

What torn bodies and gashed souls this monster, this leviathan, leaves in its wake. And a leviathan is exactly what it is, in all the possible metaphorical senses of this term (including of course the meaning given to it by Thomas Hobbes).

If one wants, one can go even further back in time, to the Biblical origins of time and, like Melville, see this leviathan as it was presented to Job by Yahweh.

Canst thou draw out leviathan with a hook? Or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down? Canst thou put a hook into his nose? Or bore his jaw through with a thorn? Will he make many supplications unto thee? Will he speak soft words unto thee? Will he make a covenant with thee? Wilt thou take him for a servant for ever? Wilt thou play with him as with a bird? Or wilt thou bind him for thy maidens? Shall the companions make a banquet of him? Shall they part him among the merchants? Canst thou fill his skin with barbed irons? Or his head with fish spears? Lay thine hand upon him, remember the battle, do no more…None is so fierce that dare stir him up: who then is able to stand before me? (Job 41:1-10)

Who indeed?

Not long after this first photograph was taken Killip went back and photographed the same location. But look how different this second photograph is. Look how things have changed in only a matter of months. It is now the middle of winter. The snow lies deep. No children can be found playing outside; there are only forlorn, isolated men, each of them huddled up against the biting cold and wind that rages in these parts, with their heads bowed down. Did they salute each other as they passed? Did they engage in conversation or heated discussion to warm the cockles of their bowels?

Most of the image conveys a scene of desolation, of emptiness, and it does not take long to realise that this is the result of much more than the harsh weather conditions. If you cast your gaze to the right, the source of the emptiness is staring you full in your face. The leviathan has gone and it has left them with nothing but its entrails. Is its disappearance temporary or permanent? At the time the picture was taken the answer was not yet known, although one suspects that in their heart of hearts they knew that it was permanent and that the closure of the shipyard was imminent. How quickly disposable profits at one end of the social scale can be transformed almost like magic – black magic – into disposable, throw- away lives at the other end.

Yet not all is seemingly lost. Amidst the desolation a message of hope can still be conjured up. The camera lens on this occasion has slightly expanded its horizons. A wall is revealed that was not seen before, and its message rings out loud and clear. ‘Don’t vote’, it exhorts. It is already a sign that the political party which once upon a time proclaimed its allegiance to the working class has deserted and betrayed them, and by doing so it has paved the way for its political enemies to complete the job of destruction and annihilation under the diktat of Mrs Thatcher. But the betrayal has also unleashed the blinkers from their eyes. Things are clearer now than they once were. The absolute contrast between black and white is there for all to see. The negative exhortation not to do something is accompanied by a positive: ‘Prepare for revolution’.

Alas, it was not to be. The forces waged against them were too powerful, too overwhelming. Within the space of a few years, the jobs and the community that went with them were destroyed and a veritable waste land took their place (as can be seen in the third photograph).

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow/ Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, / You cannot say, or guess, for you know only/ A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,/ And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, / And the dry stone no sound of water. (2)

And yet even here, amidst the bleakest possible desolation, it turns out that some roots do indeed still clutch. There on the wall to the left, the graffiti, the message, remains. It was not destroyed. No, more than that. To say ‘it was not destroyed’ might imply that it escaped destruction by accident; that it was some kind of oversight on the part of those who carried out the demolition. But I think there is something much stronger at work here. This was no accident that it was left intact. Even if the intent had been to destroy it along with everything else, it could not be destroyed.

***

Take photos otherwise they will not believe us (Franco Basaglia). (3)

As one enters the exhibition of Chris Killip’s photographs a story is recounted:

One night in 1994 my American friend John Clifford, who owned the best bar in Cambridge, took me into the middle of Boston to where the civic center and other administrative buildings now stand. These buildings were built in the 1960s on top of the old tough working class district of Scully Square, where John and his brothers were born and raised.

John pointed out to me streets that no longer existed, telling me who had lived where and in which house. Who had died in Vietnam, who had worked for the mob, who had gone to prison or ended up in politics. When I interrupted this narrative to tell him how great it was that he was telling the history of this place he spun around, gripped me by the throat and pushed me against the wall. With his raised fist clenched he said, ‘I don’t know nothing about no fucking history, I’m just telling you what happened.

We look at these photographs today, in the present, which are images of the past, and by doing so they compel us to reflect on the past and all that it entailed – for good and bad. But they do more than that. They likewise beg us to reflect on the future. But what future awaits us? ‘A people or a class which is cut off from its own past is far less free to choose and to act than one that has been able to situate itself in history.’(4)

Thirty years have passed since the final photograph was taken. For sure, the wall that contained the message has long since succumbed to the vagaries of time and destruction. But the message outlives the wall. The wall is only an outer, superficial container. It pales into comparison with the real container of the message which is our hearts and our spirit. And if the message can no longer be seen or heard on Tyneside, its echoes do continue to resound on the streets of many other places throughout the world.

There is one final photograph from Killip’s exhibition that I want to refer to. It depicts a young boy, no more than ten or eleven years old, who sits in front of a small fishing boat deep in concentrated contemplation. His face expresses immense sadness but in contrast his eyes express a depth of determination. Only the caption below the photograph can begin to reveal the inner workings of his thoughts. ‘A young boy takes to the sea again after the drowning of his father (1983).’

If only we can all find the political courage to match this young boy’s human courage, then not only will the ‘revolution’ be prepared… it might even succeed. Now wouldn’t that be an image to see…

___________________________________________________________________________

Notes

(1) See Alan Myers, ‘Evgenii Zamiatin in Newcastle’, Slavonic and East European Review, No. 68, 1990 and ‘Zamiatin in Newcastle: The Green Wall and the Pink Ticket’, Slavonic and East European Review, No. 71, 1993.

(2) T.S. Eliot, ‘The Waste Land’ in Collected Poems 1909-1962 (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), p. 63.

(3) This advice was given by Basaglia to Raymond Depardon so that a photographic record could be made of psychiatric conditions in Italy in the late 1970s. See Raymond Depardon, Manicomio: Selected Madness – Secluded Madness (Göttingen: Steidl, 2012).

(4) John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972), p. 11.