Francesca Pierini

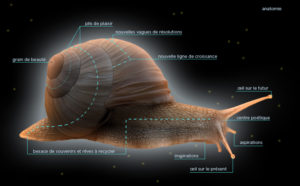

Land snails carry their home along. People like me, who have been away from home for many years, carry their lack of home along. Each burden has its own weight, I suppose.

People living out of a suitcase, if they are like me, are active but homesick; adaptable but divided; adventurous but apprehensive. And, just like snails, or Little Thumb with his bread crumbs, they leave behind a trail of personal effects that reveals the course of their journey.

I am forty-five and I have lived, so far, six and a half years in England (London), one and a half years in continental China (Harbin and Nanjing), five and a half years in Taiwan (Taipei), one year in Belgium (Leuven). I have spent five months in Thailand (Koh Siboya), and I am about to go to live in Singapore, for at least seven months. Over the last seven years or so, my two brothers have migrated to New Zealand (Wellington), and now live there with their respective families, so that my family has partially recomposed itself at the other side of the globe, in the ‘upside-down Italy,’ leaving my parents home and me the ‘mobile’ member of the family. My husband, Philippe, is from Quebec.

Of course, I am not talking about real migration, the one when one goes from Italy all the way to Minnesota to disappear underground an iron ore mine. We have all had, my brothers and I, the possibility to shape much of our lives with our own choices, a privilege few people know. We also had to work hard to recognize them and make them happen, because even if we could always count on much social and cultural capital, and tireless moral support, we had to use these assets to get somewhere by ourselves. I don’t say this because I must depict a struggle at all costs; I say it because there has been one.

Since I left for London, for the first time, when I was twenty-three, I have never had my own place; I mean a permanent place besides my parents’, so that I feel my lack of home, more than a loss, is a tangible absence, a semi-permanent condition that has lasted most of my adult life (except for the years of my first marriage).

Over the years, my own place has become a project and a task. What I call home is, alternately and confusedly, Italy, my parents, my husband, an imagined apartment, and sometimes all this tied together with the glue of my childhood memories and my plans for the future.

Italy has a strong hold on me: I feel a connection I don’t know what I would be without. Every morning, I check online the Italian newspapers; I love listening to old melodic songs; I plan on seeing parts of Italy that I haven’t visited yet, like Mantova, for example, Turin, the Alps, and I dream of going back to Sicily and Naples.

Over time, I have elaborated an idea of home into a work of the imagination that is at the same time very concrete with childhood and post-childhood details, but also fanciful, because of my discontinuous relationship with the country.

So that home is lovely most of the times, with a dreadful lining, just like a dream. In my experience, pleasant or neutral dreams can instantly turn on you. It is the atmosphere that makes the dream, not its content: one can have beautiful dreams filled with snakes and nightmares filled with fairies. Dreams play with the thin membrane that separates a safe swim above blue waters from drowning into a black depth.

Recently, I had a nightmare about two young people, a young man and a woman, chatting over coffee in a bar (bar in the Italian sense, a café, really…I specify this because ‘bar’ in English is nocturnal, in Italian is the diurnal place of breakfast). The woman realizes, while talking to the man, something so agonizing and hurtful that makes her soul leave her body. We see her soul, just like in the movie ‘Ghost,’ a much ethereal, see-through shape of herself, leaving the woman’s body, and the woman at the café, older, cynical, a rougher version of her previous self, asking the man to sleep with her, because nothing matters any longer, and nothing could hurt her. The man smiles to reveal ugly teeth.

My idea of Italy is similar. It is normally purified of all the dark moments, it is coffee with a friend on a sunny day, but then, from time to time, I get stung, I cringe, I sink under waters for a few seconds, some of my thoughts turn against me, and I know I could never go back there permanently.

Italy reminds me of the years when I was stuck and deluded, when I used to think that exceptional things were bound to happen to me just because I was me, and I was destined, if not to happiness, to an interesting life that would happen more or less by itself, and without effort. Italy reminds me of immaturity, self-entitlement, fog in the brain, incapacity to understand myself and make myself understood, to move forward, a feeling of suffocation, periods as painful as monthly punishments, my parents’ preoccupation, the aching discovery of the stagnancy of my life, the consequent panic, a deep embarrassment for not having understood more and earlier, a feeling of shame: I still feel there are so many people I should apologise to, just for having been so unprepared, unfocused, and having said so many silly things.

Many call this state ‘adolescence,’ but I know plenty of people who have sailed through it above relatively calm waters.

Except for holidays alone or with my husband, over the last decade, childhood, I think, is the last enduring happiness I have known in Italy, so that I have coagulated the past into perfectly satisfying moments (they may be enhanced, but they really happened), like the one when my brother Marcello and I were very young and my mother drove us from Rome to Florence, in the middle of the 1970s. We bought tickets to the Uffizi Gallery on the same day, and had the corridors almost all to ourselves. I remember distinctly Marcello and me chasing each other along the halls of the gallery. I remember my mother trying to turn our attention to the paintings, telling us that the Madonna del Cardellino (Madonna of the Goldfinch), for example, depicted by Raphael, a Madonna with two small children playing together in front of her legs, was the portrait of us three. It made perfect sense to me at the time; this interpretation made me stop in front of the painting for a few seconds, and obviously made me remember it indefinitely. At the time, I saw a beautiful woman who was trying to read a book in a garden while she was also minding two children playing with a small bird. One of the children, naked, was a boy, the other child, covered, was plump and curly-haired, just like me at the time. The whole thing was perfectly plausible, a very familiar scene, actually, except for the clothes the mother was wearing, her fair hair, and the bird.

The two children are actually Jesus (the naked one) and John the Baptist (me); the goldfinch symbolizes the Passion of Christ, because, the story goes, the bird got its characteristic red stain the moment Jesus got crucified. Of course, to me, the painting will always remain a family portrait from an early period: my father off to work, my brother and I playing, distracting my mother from reading, our youngest brother, Rocco, on his way but still, quite literally, out of the picture.

Maybe, since I am talking about a lack of home in adult life, the right mollusk to compare this to is not a snail, born with a home, but the hermit crab, a creature capable of making, out of its own strength, will, and imagination, a home of unique beauty, a materialized dream of comfortable perfection.

My own dream-home, my project and task has a name: “red Bialetti,” a concise formula with which my husband and I refer to it, a place filled with all our belongings currently scattered between Montréal, Maremma, Marche, Taiwan, and Singapore. There are some objects I just can’t wait to see again, like the handmade bamboo sake bottle I have bought in Kyoto, or the presents from my students in Taiwan. Most objects I have forgotten though, because I rearrange my few boxes only occasionally, every few years.

The Bialetti name comes from the fact that some time ago, while I was still living in Taipei, feeling particularly homesick, I saw a display of Bialetti machines at City Super. City Super is a fancy supermarket, in a fancy area of Taipei, specialised in high-quality imported foods and expensive foreign merchandise. The coffee-machines, so familiar to me, were carefully displayed as a collection of exotic creations (It was a little like visiting a famous aquarium at the other side of the world, say the one in Okinawa, and recognize my own goldfish swimming in it- a dream, now that I think about it, with a lining of dread to it).

The red BIaletti, at the time, seemed the nicest one to me. Now I have seen the red and transparent one, which is maybe even nicer, but I am quite sure that when the moment comes, I will remain faithful to that love-at-first-sight experience, that moment of instant recognition between me and my home-country that happened through seeing, as for the first time, one of its most traditional (yet commodified), simple (yet crafty), every-day (yet clever) objects.

Usually, I don’t even like kitchen equipment, all that petit-bourgeois design gear gets heavily on my nerves. I don’t enjoy cooking, I get immediately bored with it. If I am alone, I eat standing over the sink; if I am with my husband, I like to prepare meals with him, but it’s the ritual I enjoy, and the company, not the cooking itself. Also, we are pretty similar in that department, so we don’t judge each other. Over time, we have learnt to make a few good pasta dishes, that’s all.

Our forte is not even a dish, but homemade Cointreau, which takes 6 weeks to make. The orange has to hang in mid-air, for 3 of those 6 weeks, in a jar with pure alcohol. The fruit, over time, ‘sweats’ all its juice into the alcohol, so that, coming back home every day, one sees the alcohol getting orange-r and orange-r, the zestful drops gradually conquering the liquid.

Maybe, the day we will finally be in a real apartment, my husband and I will exchange a look of fear. Like in ‘The Graduate,’ we will perceive the obscurity the moment we reach the light, a dark well opening beneath blue waters, but for now, the thought of this ‘real’ apartment, complete with its red Bialetti and Cointreau jar, keeps us going.

If I could choose a place in the whole world for my future home, I would choose Saturnia, a small hot-spring town in Maremma I have been going to with my parents since I was very little, or one of its tiny frazioni, the even tinier satellite towns scattered around it. I have learnt to swim in those hot springs, which throughout the 1970s were very affordable. The smell of sulphurous waters, which is in theory quite unpleasant, takes me back, just like that other unmistakable (and in theory nasty) smell of burnt rubber from the underground station below my childhood apartment in Rome. The other scent that does the trick is the one of Coccoina, a paper-glue popular with kids throughout the 70s.

Saturnia is the only place that has been there since the beginning of me that does not have, to my eyes, a gloomy lining. I just want to keep it close, keep it whole, and one day, I would like to be able to inhale the scent of its waters from home while sipping coffee made with our red Bialetti.