Lamberto Tassinari

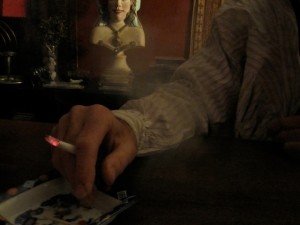

At the beginning there was nothing but smoke. Everyone was smoking so I did too. I smoked a lot even before being able to have sex. Smoke was for lovers, as Virginia. As a smoker I began with Jubek filtro, a short and funny cigarette created during Fascism to celebrate, I suppose, the African appendix, the newborn Empire. Smoking was strictly forbidden; paternal, maternal or societal authority would intervene smacking the kid, the adolescent smoker caught with the vice. To smoke, we would hide in an immense, abandoned Medicean fortress and, sitting in a circle like little indians, we would inhale a bitterish smoke and sometimes consume jocular, rapid handmade sex. The smoke would come out like a jet, expelled and propelled densely from our mouths and noses. These were very heavy times. The so called Modernity was already dead, over-killed by the horror and nonsense of the war which had ended only fourteen years before. But the ordinary people had forgotten the dead. We are lazy and slow. Each generation must start from the beginning and learn for itself. It’s not stupidity, it’s distraction; life makes us forget so that we can invest our energy in the business of living. Italy then had great passions, ideals and practical goals to achieve: smoke was absolutely necessary, it was so natural and it connected so naturally to things.

First, there was the American smoke during the years of Liberation. It was a blond and sweet tobacco that pervaded the air after the lean years of autarchy. Then there were the passionate, political years with its ideological smoke which, as everyone knows is black and filterless, black finger tips and poor, needle-smoking-times. It was for serious smokers only. I was a teenager then and I knew that women were looking for men that acted like real men. I would do my best and buy, two, three, five cigarettes, never an entire package and hide them on top of a cup- board in my room. I would smoke my Camels in front of the girls or in crowded trains and bars always holding my head like Bogart. All around me they were making a nation. Nobody would talk about cancer. Smoke then was not linked to hospitals, and statistics but to true love, beauty and romantic Hollywood deaths. Smoke was a social link at a lower and more popular level. And the offering of the small, round, white cylinder or the fire to go with it was enough to initiate a (hi)story. I never liked home-made cigarettes just as today I dislike domestic wine.

Cigarettes have to be identical, anonymous, inter- changeable, reproducible ad infinitum. I have always been obsessed by the different shapes, colors and names of objects surrounding me but a cigarette always remained a cigarette, it was immutable. People now are rolling them not for rebellious or economic reasons. They are simply searching for something personal, something upon which to leave their imprint. They content themselves with their own rolled cigarette. The majority however refuses and cannot tolerate smoke. It makes them feel guilty, they suffer a cosmic guilt. Society holds no vision, no real enemy, no future. So they hate smoke which is the target of their emptiness, their frustrated sense of morality. People need a passion now that the great ideals and battles are over, an organized and scheduled passion against nuclear death, pollution death, smoke death. People think that the body now has to be saved since the soul is already gone. Mass unhappiness. Nowadays the multitudes show the same sensibility and anguish once shown by the isolated artist.

Millions are suffering the poet’s sufferance. But it is not the same. Can smoking, this modern and progressive vice, save us from the insidious inflation of melancholy? Can the noise of the flintstone wheel percussed by the yellow thumb regenerate the heavy sense of life that used to possess humanity? Can the witty flame of a lighter and the burning of a gentle tobacco make times roar again? I’ll try. Rest assured, I’m not a nostalgic, nor a conservative, nor a man of principles, my faith has always been weak… But now I cannot tolerate anymore this outrageous attack against modernity. I confess, smoking was my last political gesture, my last hope in mankind, my last action, my last intention. So I will try, I’ll take out a hidden package of twenty Camels, I’ll open it slowly with shaking fingers, and then the bold, shiny Ronson will click. Smoke will appear in a spring afternoon and fill the sunny basement with floating gray-blue forms, and modernity will be safe, for a while.

(First published in ViceVersa magazine N. 18-19, June 1987)