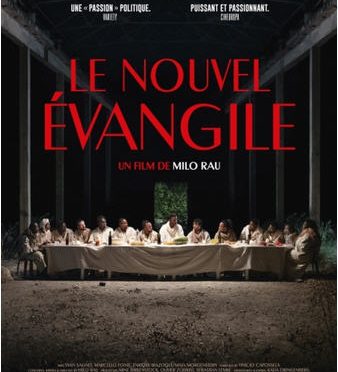

Par tradition catholique, le Christ a toujours été présent en Italie méridionale. Au siècle dernier, il l’a été aussi par sa médiation littéraire (Le Christ s’est arrêté à Eboli de Carlo Levi) puis cinématographique (Pier Paolo Pasolini et Mel Gibson). Voici qu’en 2019 à Matera, en Italie, le cinéaste activiste suisse Milo Rau en a ajoute un cran en le faisant porte-parole des exploités agricoles. Ce sel de la terre est « Le nouvel évangile » que l’Observatoire de la diversité culturelle des Lilas a eu l’excellente idée de projeter le 6 mars 2024 en présence de son acteur principal, l’activiste italo-camerounais Yvan Sagnet.

Rarement film aura percuté aussi frontalement ma propre histoire familiale. Nous sommes en 1899 dans les Pouilles, un garçon de seize ans s’apprête à émigrer comme des millions d’autres pour les Amériques. Il a refusé d’être un « bracciante » : un travailleur agricole employé à la journée et payé une misère. Les latifundia, ces grandes propriétés survivent encore par leur archaïsme sectaire dans cette Italie à peine remembrée. Avec son pécule amassé vingt ans durant, il achètera un lopin de terre et deviendra à son tour exploitant agricole. Ce jeune méridional s’appelait Giovanni Montaruli. C’était mon grand-père.

Un peuple d’immigrants à l’épreuve du migrant

Si ma famille était restée dans les Pouilles, il est possible que j’eusse hérité de ses terres. J’aurais alors été confronté au dilemme exposé dans ce pertinent docu-drama : céder aux pressions des grandes firmes en exploitant à mon tour les plus fragiles que moi ou résister avec les ouvriers agricoles pour trouver ensemble une autre manière de vivre et de travailler. Tel est aussi l’équation christique que Milo Rau nous propose de revisiter.

Le coup de génie du cinéaste activiste est d’avoir su croiser dans ce film le combat spirituel du passé avec la révolte des exploités du présent. Ce télescopage inopiné redonne toute son sens et sa brûlante actualité au sacrifice christique qui permet simultanément de faire une œuvre de cinéma et de ressembler des personnes fort différentes qui jusque là ne s’étaient pas parlé.

Voilà bien la grande vertu sinon l’originalité de ce cinéma engagé comme l’a reconnu volontiers l’activiste Yvan Sagnet que Rau a choisi justement pour interpréter le Christ. La médiatisation induite par le film qui a remporté le prix du meilleur documentaire en Suisse a en effet rendu possible les conditions d’une filière agroalimentaire éthique dans cette région ? Conséquence : la légalisation et l’amélioration de la situation de milliers de travailleurs agricoles africains migrants et souvent sans-papiers; (Pour informations www.nocap.it

Le moment transculturel

Cette mobilisation à laquelle nous assistons avec ses contradictions et ses hésitations (que le cinéaste a choisi de conserver) est aussi un pur moment transculturel. L’œcuménisme linguistique se déploie dans toute sa diversité. Le bambara, le wolof… l’italien, le français, l’anglais s’entrechoquent dans un joyeux et militant Babel sonore et musical. Elles créent de la sorte l’espace d’une hospitalité transculturelle à mi-chemin entre la langue nationale et la lingua franca du commerce mondialisé. A contrario, ce moment désigne aussi aux pouvoirs autocrates le nouveau bouc émissaire : le migrant sans papier souvent africain. Le projet de « remigration » de l’extrême droite allemande ne laisse hélas pas de doute à cet égard.

Kairos

Kairos

Tel est le « Kairos », l’occasion dont Rau, comme à son habitude, sait saisir les enjeux et réussit à la mettre en scène. Matera était à cet égard le lieu idéal. Non seulement à cause du cinéma plus haut mentionné, mais parce qu’elle fut naguère, la ville la plus misérable d’Italie avant d’être en 2019 élevée au rang de capitale culturelle de l’Europe. Matera toutefois n’a pas coupé complètement avec la misère puisqu’elle abrite aussi le plus grand ghetto de travailleurs agricoles migrants de l’Italie méridionale. Voilà bien l’occasion pour croiser le profane et le sacré tant du point de vue éthique, esthétique et politique. Cela donne un curieux, mais très efficace objet social hybride qui, comme les graffiti de Banski, casse les codes de la représentation classique et innove la manière de faire événement.

La distanciation de Brecht et les Mystères

Pour y arriver, le réalisateur activiste va appliquer deux méthodes éprouvées . La première, la plus récente, est celle de Berthold Brecht qui a théorisé la distanciation de l’acteur avec son personnage. Le but est de révoquer, derechef, toute tentative d’identification. En étant le témoin de la fabrication du film et de sa mise en scène effective, le spectateur est toujours renvoyé à son rôle politique d’observateur et d’acteur potentiel du réel. Étonnante mise en abyme où la fiction se confronte à la réalité, où le profane permute le sacré et le déconstruit.

La seconde est la plus ancienne est la réactivation de la grande tradition des « Mystères ». Au moyen-âge ce fut un formidable outil pédagogique utilisé par l’Église pour instiller la foi au peuple des villes souvent illettré. La passion du Christ en est le cœur. La ville entière y participe dans un formidable élan d’espérance carnavalesque et populaire. Cette tradition a donné naissance par l’entremise de Rabelais à la fiction moderne : le roman.

Émotion, motion, démotion

Mais chez Rau la parodie rabelaisienne si drolatique brille par son absence. C’est d’ailleurs la limite de cet exercice qui reste obstinément dans le registre social. En voulant réduire sciemment la dramatisation du mystère, en gommant au maximum sa dimension spirituelle, Rau affaiblit sa valeur esthétique. Or la Mimesis, l’imitation bien comprise induit l’ironie qui est le fondement de l’art moderne authentique. Car par l’art, le sacrifice humain, le bouc émissaire, n’est plus la condition nécessaire pour faire l’unité du groupe. Rau le sait bien, mais s’en méfie. Malgré quelques beaux et grands moments d’émotion (dont l’une ô combien troublante dans laquelle un jeune homme italien voulant jouer un soldat de Ponce Pilate torturant le Christ se transforme sous nos yeux en véritable monstre de cruauté), plusieurs scènes sont bâclées, ou à peine esquissées. L’impression qui s’en dégage demeure celle de l’improvisation, de l’inachevé. Encore, un sympathique fourre-tout que les cinéastes militants ont le don de trousser. (Deux mois plus tôt dans la même salle Yannis Youalountas présentait son nouveau documentaire intitulé « Nous n’avons pas peur des ruines », mais moins réussi). On me dira que cela est assumé d’emblée. Certes, mais à trop vouloir court-circuiter l’émotion et circonscrire l’ironie, on réduit le film à une plaisante pochade, une aimable répétition d’amateurs, un théâtre social utile bien sûr, mais conjoncturel qu’il faut consommer avant que la date de préemption n’échoie. Dommage.

Encore un effort monsieur Rau !

Les dictateurs sont souvent des clowns tristes qui pour se dérider projettent leurs passion tristes cher à Spinoza sur le monde devenu leur carré de sable personnel. Là ils peuvent faire et défaire leur château à leur guise, comme des enfants capricieux, colériques et frustrés qu’ils ont été. La scène du « dictateur » où Charlot/Hitler fait virevolter le globe sur ses pieds est éloquente à cet égard. En vérité les dictateurs cherchent leur double qui les déridera, un peu beaucoup, passionnément de leur mélancolie rédhibitoire. On raconte qu’Hitler s’est fait souvent projeter le film de Charlot tout hilare de s’être fait démasquer par un sosie qui lui ressemblait tant. Je ne sais pas si cette histoire est vraie, mais une chose est sûre. Chaplin était un clown triste qui se jouait de l’esprit de sérieux et Hitler un triste clown qui se prenait au sérieux. L’un était ironique, l’autre sardonique. La semaine du 24 février lors de la marche l’Ukraine à Paris, une militante ukrainienne rappelant les anciennes déclarations d’Alexeï Navalny pour conserver l’Ukraine dans le giron russe, l’avait comparé à un clone de Poutine. Cette affirmation navrante sinon maladroite quelques jours après la mort de ce dissident exemplaire n’est cependant dépourvue de vérité. Car si Navalny ressemblait au despote du Kremlin, c’est parce que Poutine face à lui était devenu sa caricature, une marionnette ridicule et piaffante.

Les dictateurs sont souvent des clowns tristes qui pour se dérider projettent leurs passion tristes cher à Spinoza sur le monde devenu leur carré de sable personnel. Là ils peuvent faire et défaire leur château à leur guise, comme des enfants capricieux, colériques et frustrés qu’ils ont été. La scène du « dictateur » où Charlot/Hitler fait virevolter le globe sur ses pieds est éloquente à cet égard. En vérité les dictateurs cherchent leur double qui les déridera, un peu beaucoup, passionnément de leur mélancolie rédhibitoire. On raconte qu’Hitler s’est fait souvent projeter le film de Charlot tout hilare de s’être fait démasquer par un sosie qui lui ressemblait tant. Je ne sais pas si cette histoire est vraie, mais une chose est sûre. Chaplin était un clown triste qui se jouait de l’esprit de sérieux et Hitler un triste clown qui se prenait au sérieux. L’un était ironique, l’autre sardonique. La semaine du 24 février lors de la marche l’Ukraine à Paris, une militante ukrainienne rappelant les anciennes déclarations d’Alexeï Navalny pour conserver l’Ukraine dans le giron russe, l’avait comparé à un clone de Poutine. Cette affirmation navrante sinon maladroite quelques jours après la mort de ce dissident exemplaire n’est cependant dépourvue de vérité. Car si Navalny ressemblait au despote du Kremlin, c’est parce que Poutine face à lui était devenu sa caricature, une marionnette ridicule et piaffante. et sa grandeur. Poutine le savait et le redoutait. Navalny a fait le pari que la prison dans laquelle il serait enfermé en revenant en Russie était aussi celle de Poutine même si elle était dorée. Pari risqué et dangereux, certes. Mais pari calculé. Voici à ce propos ce qu’en dit Vladimir Jankélévitch : « L’ironie qui ne craint pas les surprises, joue avec le danger… Elle l’imite, le provoque, le tourne en ridicule… même elle se risquera à travers les barreaux, pour que l’amusement soit aussi dangereux que possible, pour obtenir l’illusion complète de la vérité ; elle joue de sa fausse peur, et elle ne se lasse pas de vaincre ce danger délicieux qui meurt à tout instant. Le manège, à vrai dire, peut mal tourner, et Socrate en est mort ; car la conscience moderne ne tente pas impunément les créatures monstrueuses qui terrorisèrent la vieille conscience ».

et sa grandeur. Poutine le savait et le redoutait. Navalny a fait le pari que la prison dans laquelle il serait enfermé en revenant en Russie était aussi celle de Poutine même si elle était dorée. Pari risqué et dangereux, certes. Mais pari calculé. Voici à ce propos ce qu’en dit Vladimir Jankélévitch : « L’ironie qui ne craint pas les surprises, joue avec le danger… Elle l’imite, le provoque, le tourne en ridicule… même elle se risquera à travers les barreaux, pour que l’amusement soit aussi dangereux que possible, pour obtenir l’illusion complète de la vérité ; elle joue de sa fausse peur, et elle ne se lasse pas de vaincre ce danger délicieux qui meurt à tout instant. Le manège, à vrai dire, peut mal tourner, et Socrate en est mort ; car la conscience moderne ne tente pas impunément les créatures monstrueuses qui terrorisèrent la vieille conscience ».

Kairos

Kairos