Ángel Mota Berriozábal

Observando el río San Lorenzo, desde el oxidado y vetusto puerto de Montreal, seguí las líneas del agua, los trozos de hielo que se escurren por la corriente. Vorágine que azotó navíos por tantos siglos. Una de las aguas más peligrosas del mundo por sus numerosas corrientes y diversidad de fondos marinos. Y en ese río, grisáceo, imaginé todo el estiércol que ha sido evacuado en su organismo. El alcalde de la ciudad, Dennis Coderre, decidió abrir las cañerías de la urbe para verterlas al San Lorenzo. Con esta observación, desde el puerto, pensé con ese calor anormal de otoño, en los cambios climáticos, provocados por la contaminación y el exceso industrial humano. Me sentí y siento como microorganismo, parásito, entre fábricas, humo, mierda y la prosa de la destrucción urbana. Lo cierto no veía ninguna solución a esta depredación y paulatino deterioro de todo en la isla de Montreal y el mundo.

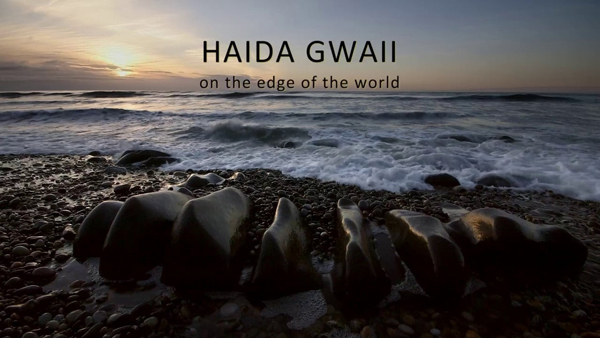

Por ello, cuando mi amiga mexicana-canadiense Dafne Romero me invitó, desde la British Columbia, a ver el documental que coordinó como productora; Haida Gwaii, at the Edge of the World, nunca imaginé que ir a ver su trabajo en la Universidad de Quebec en Montreal, donde se proyectó, pudiese obsequiarme eso que precisamente me hacía falta; esperanza y deseos de volver a creer y sembrar para revivir la tierra donde vivo.

Haida Gwaii, at the Edge of the World fue dirigido por Charles Wilkinson, obtuvo los premios a mejor documental en los prestigiosos festivales de cine de Toronto, Vancouver y Nueva York. Wilkinson, invitado por Dafne, luego de un proyecto que hicieron juntos sobre la nación Haida, accedió a volver a las míticas y remotas islas al noroeste de Canadá para contar cómo la nación indígena de las islas y la población anglosajona e inmigrante, han logrado salvar la naturaleza, cultura, ecosistemas, vida social y cultural de este paraje, casi edénico.

Las islas Haida Gwaii, antes denominadas por el colonialismo inglés: Charlotte Islands, son cuna y casa de una de las civilizaciones indígenas más desarrolladas al norte de México; la Haida. Desde tiempos inmemoriales esto nativos han sabido emplear los árboles gigantes; cedros, tuyas, piceas para construir sus casas, canoas, cestas, ropa, sombreros, redes, etc. Los árboles no solo son parte de uno o varios ecosistemas, “son una función de vida, hasta nuestros días −me explicó Dafne en casa de la Mrs. Stein de la comunidad mexicana de Montreal; Cristina Boilés−, en donde cada partícula de los habitantes y de sus hogares depende y está formado en relación con los árboles.” Casas y tótems, artesanías, cajas y demás manufacturas, de uso diario, despertaron el interés de los primeros colonos y por ello; “una parte fundamental de la cultura Haida y de su sobrevivencia −me afirmó Dafne, mientras hacía su maleta, con miras a tomar el avión, in extremis, rumbo a Estambul−, es el uso y trabajo sobre madera.” Los símbolos, los tótems se vuelven no solo una identidad y modo de vivir, religión de una cultura de ocho mil años, sino un modo de vivir y de ser vistos y reconocidos en el mundo por la calidad y belleza de sus obras de arte. Las cuales se hayan en tantos museos en el mundo. “De ahí que los árboles, fuente de vida ecológica y humana, se vuelven a la vez un medio de defensa cultural y social, “pues su fama –dijo Dafne, sentada entre pinturas y vasijas mexicanas puestas en todos los muros de la sala− ha logrado que muchos países deseen proteger este patrimonio de la humanidad.” De hecho, si hacemos un vínculo antropológico con el arte Haida y su función escatológica, las casas de madera en donde antes vivían representaban seres sobrenaturales o animales, que protegían a quienes durmieran dentro del hogar. La madera se vuelve un alma protectora, tal y como la madera tallada de obras de arte se ha vuelto una protectora de su cultura y contra la depredación.

“Los Haida han logrado sobrevivir –me explicó la mexicana-canadiense, quien ha hecho varios proyectos antropológicos sobre iconografía y simbolismo en la zona y ahora realiza una muestra fotográfica de tótems en Berlín−, porque su arte y alto grado de desarrollo les ayudaron a no desparecer con la colonización inglesa y sus leyes racistas, como lo fueron las leyes que les prohibían el uso de su lengua y religión, o la creación de escuelas residenciales donde los quisieron asimilar a la cultura occidental. De hecho, los europeos mismos que se asentaron en la isla, desde el siglo XIX, se unieron a los nativos para preservar la isla, su naturaleza y riqueza.” Cierto es, sin embargo, que desde el siglo XIX el imperio británico no vio en las islas otro interés que el de explotar los recursos naturales, y entre ellos, principalmente, los árboles gigantes y milenarios. Cientos de años de vida cayeron con cierras y cables, ochocientos años de un cedro o picea acabaron en astillas y bloques de madera para ser empleados en barcos, casas y muebles en Europa. El resultado de esta mutilación económica es que se cortó 70 % de los bosques de Haida Gwaii, lo que se convirtió en un abismo y destrucción ambiental, ecológica y social.

Sí, cortar tan gran cantidad de árboles equivale a cortar la vida de los Haida y su saber hacer y vivir. La mutilación de la tierra no solo la desnuda y priva del oxígeno, casa y techo a animales, el sustento de insectos, aves y mamíferos, 70% de talla es la mutilación de una cultura y de la esperanza de un planeta que todavía pueda salvarse de la mutilación de su existencia. He ahí que Dafne Romero me haya dicho que Haida Gwaii es una metáfora y ejemplo del mundo. Su caso no debe ser visto como único, sino que debe aplicarse a toda la tierra. Como lo que sucede con el río San Lorenzo y la descarga de excrementos, con la posible construcción de una estación petrolera en Cocouna; santuario de las ballenas beluga, o con el futuro paso de un oleoducto por ríos y bosques de la provincia de Quebec.

La estructura del documental da cuenta de la complejidad del fenómeno en Haida Gwaii, y por ende de la complejidad de las soluciones y conflictos que se crean en la protección o explotación de los recursos. De ahí que vemos cómo, a través de un recorrido en el tiempo, los indígenas Haida bloquearon carreteras en las islas, impidiendo que los camiones de las industrias madereras prosiguiesen su labor, visitaron la corte suprema, redactaron artículos, fueron a la ONU. Nada de lo cual hubiese tenido el mismo resultado, según lo que se muestra en la cinta y me explicó Dafne, sin la unión de la nación Haida con los “blancos.” Luego de lograr frenar el deterioro de los bosques, los Haida pudieron comprar la mayor parte de las islas y detener así la erosión total de los bosques. Además de que estos indígenas aplican ahora sus propias leyes y autoridad en casi todo el territorio, como resultado de una lucha legal con el gobierno de Canadá.

De la fuerza de voluntad, de la organización de todos los habitantes, sin importar origen racial o étnico, se propuso dar alternativas al desarrollo económico de las islas, pues no bastaba −muestra el corto−, con defender y bloquear carreteras. Se propuso hacer otro tipo de economía, como la compañía de Dafne, la cual confecciona comida con algas, entre ellas; “lasaña”, o que los colonos planten y vendan verduras orgánicas, o que el turismo, uno de los motores principales de la región, se haga con consciencia ecológica, en donde se invita y recibe a un turismo que respete tanto la fauna y la flora como el modo de vida y cultura de los habitantes.

Todavía se cortan árboles en los sectores privados que ofrece el gobierno canadiense a las compañías forestales y en las mismas tierras Haida, a causa de la corrupción. “La corrupción –me previno Dafne, ahora ya preparando la cena para los miembros de la revista Viceversa a los que invitó, con esa gran generosidad y altruismo que le he conocido por años−, es un problema en la comunidad Haida. A pesar de todo el trabajo por frenar la deforestación, varios indígenas se dejan sobornar y venden cientos de hectáreas de árboles centenarios.” De este modo, la lucha no solo es contra las grandes empresas de fuera sino contra el alma misma de quienes viven adentro. “Pero, lo importante −me deja ver la mexicana-canadiense−, es que la tradición cultural y política Haida es la que rige las islas y con ello las leyes de protección ambiental y la necesidad de preservar los recursos por un bien colectivo es lo que prima en las decisiones y vida locales.”

De hecho, podemos observar en la cinta la influencia del arte y cultura Haida en la manera cómo se manejan las imágenes. Existe una poética intrínseca en las tomas. Dafne me dice al respecto que, precisamente uno de los objetivos del documental es hacerlo poético, artístico, como las obras de los Haida. En este sentido, At the Edge of the World cobra un sentido casi totémico en su representación misma. La poética de las imágenes es como la poética del arte indígena representado en sus cajas, cestas, mantas y canoas. Un ejemplo es la escena constante de una ballena, de su cola. Es como si esta ballena fuera la que acompañase la barca del director o equipo de producción y sobre todo que protegiese Haida Gwaii, tal y como tiene por función el animal representado en las imágenes totémicas o los animales pintados o esculpidos en las canoas. Otro ejemplo es la superposición de imágenes de árboles, vistos desde cerca, como protectores o cuya importancia se realiza dentro de un ecosistema. Función diversa a la imagen de la mecánica o de reproducción de objetos en serie, como son los muebles, casas o papel publicitario, fruto de la deforestación desmedida. De esta forma, en la cinta, las imágenes de los árboles se vuelven simbólicas y útiles, pero no útiles en el sentido de la reproducción mecánica de un objeto o de un producto en serie, sino necesarios como seres vivos y actuantes con nosotros. Como lo afirma el filósofo alemán Walter Benjamin en su texto; “La obra de arte en la época de su reproducción técnica”; la poética de la cinta refleja “un aura.” El aura para Benjamin es la autenticidad del objetivo simbólico y cultural de la obra de arte o el espacio natural, y a lo cual tenemos un acceso directo. Esto es; el documental no solo es un espacio cinético de información, hecho a través de la tecnología que toma y saca a la naturaleza, animales o sus habitantes de un espacio auténtico para luego reproducirlo en serie a la mayor cantidad de personas posibles, solo con fines comerciales, o para despojar al árbol de su función original, sino que, por medio de símbolos en la cinta y de un arte fotográfico, vuelve al documentario un arte vivo y totémico.

A este respecto, recordemos que para los Haida la orca, el oso o cualquier otro animal esculpido en un tótem, como figura principal, así como los otros animales tallados en el árbol, cuentan la historia de un clan y pueden ser a la vez protectores del mismo o de un jefe. Las figuras pintadas en las casas son el animal que cuida a los que viven dentro y la madera misma es la piel del animal, los pilares son los huesos. La casa, las cajas y canoas tienen vida propia, dada por la obra de arte de los animales dibujados o esculpidos. De ahí que el documental se presente, entre otras cosas, como una escultura Haida, una obra de arte que va más allá de su función social o mediática de reproducción en serie, pues al retomar la escatología de esta nación se muestra como ánima que cuida, protege y guía a los personajes y personas entrevistadas y a todos los actos y sitios que vemos. Se respetó así la tradición y creencias Haida y con ello se dio un valor mismo simbólico poético al documental. Como me dijo Dafne: “todo lo que se filmó, dijo y preparó tuvo que ser aceptado y comentado por el jefe de la nación y en acuerdo respetuoso de su nación.”

Cuando acabamos de ver el documental, nos parece que Haida Gwaii es el Edén tan anhelado y que, tal vez, sea uno de los últimos recónditos de la tierra en este estado natural, en equilibrio ecológico y con un modo de vida sustentable, “sin embargo −nos previene Dafne−, el documental no lo hicimos para mostrar a la gente que esto es el paraíso o para que todos se vengan acá –rio−, sino para que todos hagan algo similar desde donde viven. Cada uno puede hacerlo.”