An oxymoron by excellence, Canadian literature offers a number of singularities, especially when it is written by members of an immigrant community. Italian-Canadian literature is a case indeed. Although it may resemble postcolonial literature, it differs from it in many ways. It can be understood, of course, through the book, and thus reveals the ecosystem of languages that produces and promotes its circulation. So let’s start at the beginning, with “the influence of the book”, the title of the first Canadian novel. What was the influence of Italian books in Canada ?

An oxymoron by excellence, Canadian literature offers a number of singularities, especially when it is written by members of an immigrant community. Italian-Canadian literature is a case indeed. Although it may resemble postcolonial literature, it differs from it in many ways. It can be understood, of course, through the book, and thus reveals the ecosystem of languages that produces and promotes its circulation. So let’s start at the beginning, with “the influence of the book”, the title of the first Canadian novel. What was the influence of Italian books in Canada ?

For publication in Italian alone is no longer the only criterion for appreciation. Present in Sulpician libraries as early as the 17th century i, the Italian-language book immediately asserted itself as an index of the ‘transculturation’ in action in this rapidly changing colonial society: a publishing constant right up to the present day.

Mass emigration to Canada, ‘the last frontier “ii at the turn of the last century, created the conditions for its rise. It was the Italian press network, first the channel of communication for immigration agents and then for Fascist associations, which would later serve as its matrixiii. On the eve of the Second World War, the Italian community numbered some 100,000 expatriates, an ideal readership for the contributors to these newspapers.

Gli Italiani ‘veri’

The first to break the ice was Mario Duliani (1885–1964). La Città senza donne (1944) is a first-person account of his internment in labour camps during the war, along with 600 of his compatriots. But the book was first written in French, before the author translated it into Italian the following yeariv. Italian publisher Cosmo Iannone reissued it in 2018v.

This linguistic versatility is characteristic of many Italian writers like Giose Rimanelli. This brilliant writer, whose reputation was tarnished by his youthful adherence to Fascism, was the subject of his first novel, il tiro al piccione. This rare example of the literature of the vanquished was to seduce Cesare Pavese just before his suicide. The novel was eventually published by Elio Vittorini in Mondadori’s prestigious ‘Medusa degli Italiani’ collection. Rimanelli published his other novels in Italy, but lived until his death in the United States and Canada, teaching at their leading universities. In 1953, he even edited the weekly Il Cittadino canadese. As a professor at the University of British Columbia, he took an interest in Canadian literature, and wrote an acclaimed essay, Modern Canadian Stories, (McGraw Hill-Ryerson Press 1966), a landmark in Canadian literature. Although his novels were often written in Italian, it was in English that he published Benedetta in Guysterland (Guernica, 1993), which won the prestigious American Book Award the following year. Four years later, he published Accademia, a novel about the ups and downs of campus life. Molise and Other Poems were published in Ottawa (Legas 1998).

Rimanelli typifies the ever-present paradox of the Italian writer abroad. His linguistic versatility makes him invisible in one or other of the national literature, even though he contributes to making them better known ! Publishing houses that publish exclusively in Italian in Canada are an exception, and often on the initiative of the authors themselves when they don’t publish directly in their mother country. Such is the case of Camillo Carli, founder of the influential weekly Tribuna italiana (1960–1980), arguably the best title in the Italian press. His novel La giornata du Fabio was first published in Italy (Lalli 1984), then translated into French by Maurizia Binda, (Guernica 1991); Tonino Caticchio self-published ‘La poesia italiana del Québec’ (1983); Romano Perticarini of Vancouver wrote his poems in Italian, collected in Via Diaz, in a bilingual edition, translated into English by Carlo Giacobbe, (Guernica 1988); Filippo Salvatore published Tuffo e Gramignia (Simposium, 1977) before tran slating it under the title: Suns of the Darkness (Guernica 1980); Claudio Antonelli, another Istrian, remains faithful to Dante’s language: Scritti canadesi, partenze e ritorni di un italiano a l’estero, a collection of almost 200 chronicles and lectures on this theme, published in 2002 in Montreal by Losna & Tron. He will publish L’italiano; lingua ‘in tilt’, a kind of dictionary of the Italian language in the test of new technologies (Edarc edizioni, Firenze 2014). He does it again with Cari italiani, le mie lettere a BSV, his digital chronicles (Edarc edizioni, 2017).

slating it under the title: Suns of the Darkness (Guernica 1980); Claudio Antonelli, another Istrian, remains faithful to Dante’s language: Scritti canadesi, partenze e ritorni di un italiano a l’estero, a collection of almost 200 chronicles and lectures on this theme, published in 2002 in Montreal by Losna & Tron. He will publish L’italiano; lingua ‘in tilt’, a kind of dictionary of the Italian language in the test of new technologies (Edarc edizioni, Firenze 2014). He does it again with Cari italiani, le mie lettere a BSV, his digital chronicles (Edarc edizioni, 2017).

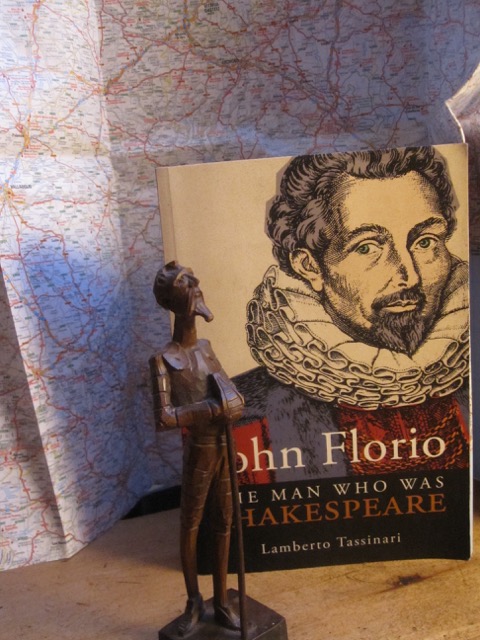

But Lamberto Tassinari is undoubtedly the most original of all. Director and co-founder of ViceVersa magazine, in 2009 he published the first edition of his landmark essay « Shakespeare? E il nome d’arte di John Florio ». This was followed by the English translation by William McCuaig (Giano 2013), and finally the French translation by Michel Vaïs, published in Paris (le bord de l’eau, 2016) under the title John Florio alias Shakespeare. The German edition is scheduled for 2024. As the title suggests, the Florentine-born writer authoritatively defendsvi the renewed thesis that Shakesperare is the son of an Italian exile of Jewish origin. A tutor to the English nobility and secretary to the Queen, Florio was, among other things, a lexicographer and translator of Boccacio and Montaigne into English! His position at the heart of the nascent British literature is no stranger to the posture of ‘the margin’ that the great writer Paul Valéry, himself of Italian origin, used to define Italianity. “…Advantage of a position on the fringe’.

But Lamberto Tassinari is undoubtedly the most original of all. Director and co-founder of ViceVersa magazine, in 2009 he published the first edition of his landmark essay « Shakespeare? E il nome d’arte di John Florio ». This was followed by the English translation by William McCuaig (Giano 2013), and finally the French translation by Michel Vaïs, published in Paris (le bord de l’eau, 2016) under the title John Florio alias Shakespeare. The German edition is scheduled for 2024. As the title suggests, the Florentine-born writer authoritatively defendsvi the renewed thesis that Shakesperare is the son of an Italian exile of Jewish origin. A tutor to the English nobility and secretary to the Queen, Florio was, among other things, a lexicographer and translator of Boccacio and Montaigne into English! His position at the heart of the nascent British literature is no stranger to the posture of ‘the margin’ that the great writer Paul Valéry, himself of Italian origin, used to define Italianity. “…Advantage of a position on the fringe’.

Italian-Canadians

The intersection of languages and cultures is also at the heart of the editorial project of the transcultural magazine ViceVersa. Published in Italian, French and Italian, this bimonthly magazine, printed in Montreal from 1983 to 1996 and now available digitally (www.viceversaonline.ca), is considered to be the most innovative Canadian editorial project of the end of the last centuryvii. In these pages, we bring together the key players in Italian-Canadian publishing ‘from sea to sea’. Among them is Antonio d’Alfonso. Founder of Editions Guernica (1977), this publisher, who is also a poet and translator, worked for 33 years to make the authors of the ‘two solitudes’ known in the other language. In the world’s 2nd largest country, the two solitude once explored by writer Hugh McLennan among the descendants of the two colonial powers now extends to migrants and First Nations.

The intersection of languages and cultures is also at the heart of the editorial project of the transcultural magazine ViceVersa. Published in Italian, French and Italian, this bimonthly magazine, printed in Montreal from 1983 to 1996 and now available digitally (www.viceversaonline.ca), is considered to be the most innovative Canadian editorial project of the end of the last centuryvii. In these pages, we bring together the key players in Italian-Canadian publishing ‘from sea to sea’. Among them is Antonio d’Alfonso. Founder of Editions Guernica (1977), this publisher, who is also a poet and translator, worked for 33 years to make the authors of the ‘two solitudes’ known in the other language. In the world’s 2nd largest country, the two solitude once explored by writer Hugh McLennan among the descendants of the two colonial powers now extends to migrants and First Nations.

In this perspective, D’Alfonso publishes his compatriots of Italian origin. He played a pivotal role as  a pioneer and mediator not only for his own community, but for Canadian publishing as a whole. A writer and filmmaker himself, he won the Trillium Award for his body of work, which includes some forty titles, including In Italics : In Defence of Ethnicity (Guernica 1996) Un vendredi du mois d’août (Leméac 2004) and Two-Headed Man : Collected Poems 1970–2020 (Guernica Editions, 2020). His most recent essay, The Italian Canadian Writer (Exthasis 2023), is an impressive survey of this young literature.

a pioneer and mediator not only for his own community, but for Canadian publishing as a whole. A writer and filmmaker himself, he won the Trillium Award for his body of work, which includes some forty titles, including In Italics : In Defence of Ethnicity (Guernica 1996) Un vendredi du mois d’août (Leméac 2004) and Two-Headed Man : Collected Poems 1970–2020 (Guernica Editions, 2020). His most recent essay, The Italian Canadian Writer (Exthasis 2023), is an impressive survey of this young literature.

But while his publishing house publishes in all three languages, it is in the English-speaking world that Guernica will make its mark. And with good reason: most of the 2nd and 3rd generation Italian community now speaks English, the” lingua del pane”. In 1988, in Vancouver, The Association of Italian Canadian Writers was founded, with the Bressani Awardviii as its prize. Both the number of members and the anthologies that bring them together have multiplied. To celebrate their 30th anniversary, the AICW published Anthology of Canadian writing (Longbridge Books, 2018), bringing together some one hundred contributions in three languages. To account for this production, the academic world is also structuring and diversifying. Joe Pivato of Arthabasca University is leading the way. While holding the Mariano Elia Chair in Italian-Canadian Studies at York University (1987-88), he taught the first course on Italian-Canadian literature : Contrasts: Comparative Essays on Italian-Canadian Writing (Guernica 1985–1991). Other publications include: Echo: Essays on Other Literatures (1994), The Anthology of Italian-Canadian Writing 2015, Longbridge Books, Montreal – and most recently

. The journal ‘Italian Canadiana’, an official periodical of the ‘Centro canadese scuole’, will periodically report on research in this field.

As for novels and short stories, Franck Paci led the way with a realistic trilogy: The Italians – 1978 – . Black Madonna – 1982 – . The Father – 1984 – , all published by Oberon Press. Other authors entered the breach: Michael Mirolla, current co-editor of Guernica, The Formal Logic of Emotion – Signature Editions, 1991 – , End of the World, – Black Moss Press, 2021 – and more recently The Collection Agency Files – Exile, 2023 – , and Genni Gunn – On the Road, 1991 – . But the one who really makes his mark is Nino Ricci. Lives of the Saints – Cormorant Books, 1990 – , the first novel in a trilogy, immediately won him the Governor General’s Novel Award, Canada’s highest literary distinction. In 2003, Nino Ricci published Testament – Harperone 2002 – , a fictionalized biography of Jesus Christ, and won the Trillium Award. The Origin of species, – Other press edition 2010 – earned him yet another Governor General’s Award, arguably making him the most successful Italian-Canadian novelist of his generation.

Women Writers ‘alla ribalta’

The women writers are not to be outdone. Mary di Michele and Caterina Edwards established their voices in Western Canada and Toronto. The former with Tenor of Love – Viking Canada, 2004 – Bicycle thieves, Toronto, ECW, – misFit book, 2017 – and the latter with The Sicilian Wife – Linda Leith Publishing, 2015 – . In Montreal, it’s Mary Melfi who makes her difference heard in her poetry, A Queen is holding a Mummified Cat – Guernica, 1982 – as well as in her theatre – Foreplay and My Italian Wife, Guernica, 2012 – . The surrealism of her poetic universe, punctuated by abrupt phrasing and populated by surprising, lapidary images, reflects the inequalities of a society imbued with progress. Her latest opus, Welcome to Hard Times – Ekstasis, 2023 – , is no exception. Her astonishing memoir Italy revisited – Guernica, 2009 – , translated into French in 2015 by Claude Beland – Triptyque, 2015 – , has earned her well-deserved recognition.

Now it’s the women who are setting the pace. Two names stand out. Licia Canton, co-editor of Acce nti magazine – www.accenti.ca – , which also includes Longbridge Editions, was also a former president of AICW. Author of a collection of short stories, The Pink House and Other Stories – Longbridge, 2018 – and a short novel; Almond Wine and Fertility – Longbridge, 2008 – , she has also coordinated a number of anthologies on women, the latest of which Here and Now: An Anthology of Queer Italian-Canadian Writing – Longbridge Books, 2022 .

nti magazine – www.accenti.ca – , which also includes Longbridge Editions, was also a former president of AICW. Author of a collection of short stories, The Pink House and Other Stories – Longbridge, 2018 – and a short novel; Almond Wine and Fertility – Longbridge, 2008 – , she has also coordinated a number of anthologies on women, the latest of which Here and Now: An Anthology of Queer Italian-Canadian Writing – Longbridge Books, 2022 .

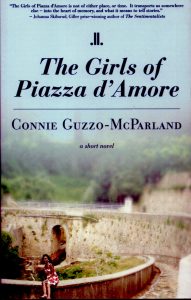

Connie Guzzi-McParland now presides over the destiny of Editions Guernica. She published The Girl of piazza d’Amore, – Linda Leith Publishing, 2013 – a short novel about her childhood, followed by The Women of Saturn – Innana 2017 – .This book and the first , , were merged into one novel and translated into Italian and published by Rubbettino Editore in 2021. In 2022, she published the biography of Italian Canadian opera singers, Louis and Gino Quilico, An Opera in 3 Acts, also published simultenaously in French -Un opéra en 3 Actes- by Linda Leith Publishing, 2022.

Italo-Quebecers

A minority within a minority, the publishing activism of French-speaking Italophones is more reserved. The first to make a name for himself, and to make his claim loud and clear, was Marco Micone. His plays such as Gens du silence – 1980 – , Addolorata –1984 – Déjà l’agonie, – 1988 – evoke the paradox of the immigrant son imprisoned by his parents’ silence and … by his trilingualism, which should normally emancipate him. His plays are collected in Trilogia – VLB, 1996 – , followed by Migrances – VLB, 2005 – and On ne naît pas Québécois, on le devient, – Del Busso éditeur, 2021 – .

Unlike their English-speaking colleagues, French-language Italian publishers don’t capitalize on their origins. Antonio del Busso, born in Spinete, founded Boréal, the flagship of Quebec publishing, directed Fides, the historic house of Quebec publishing, and then the Presses universitaires de Montréal. His namesake, however, defend a catalog focused on Quebec political history, as evidenced by the books of Claude Corbo, former rector of the Université du Québec à Montréal, also of Italian origin and author of L’échec de Félix-Gabriel Marchand [2015] and Tocqueville chez les perdants [2016]. The same applies to Liber https://www.editionsliber.com. Founded in 1990 by Giovanni Calabrese, it specialises in the humanities and philosophy.

Among female writers, it’s Carole David, whose mother is Italian, who stands out. She took part in the anthology Quêtes – Guernica, 1983 – , which brought together eighteen Italian-Quebec writers, and published some twenty books, including Terra vecchia – Les Herbes rouges, 2005 – , Impala, – Les Herbes rouges, 1994 – and Hollandia, – Héliotrope, 2011 – . Francis Catalano rediscovered his Italia n origins when he took part in the same anthology. Since then, he has continued to explore his Italian roots, both through translations of contemporary Italian poets such as Valerio Magrelli, Fabio Scotto and Antonio Porta, and through his own poetry: Panoptikon, [Triptyque, 2005], Qu’une lueur des lieux, Douze avril, [Écrits des forges, 2018] and his first novel, On achève parfois ses romans en Italie, [l’Hexagone, 2012] and Ihis latest poetry book : Climax 2023 ( Mains Libres)

n origins when he took part in the same anthology. Since then, he has continued to explore his Italian roots, both through translations of contemporary Italian poets such as Valerio Magrelli, Fabio Scotto and Antonio Porta, and through his own poetry: Panoptikon, [Triptyque, 2005], Qu’une lueur des lieux, Douze avril, [Écrits des forges, 2018] and his first novel, On achève parfois ses romans en Italie, [l’Hexagone, 2012] and Ihis latest poetry book : Climax 2023 ( Mains Libres)

At the end of this dense and all-too-brief panorama, it’s timely to ask whether Italian-Canadian literature is the product of ultraliberal consumerism, or the culmination of emancipation assumed by a mature immigrant community ? Ottawa academics William Anselmi and Kosta Gouliamos argue for the first side of the equation in Elusive Margin – Guernica 1998 – , while Franco Loriggio explores the second in the essay he once edited: Social pluralism and Literary History – Guernica 1996. In this period of identity withdrawal, will his fertile exchange with Italian-Canadian literature endure? These questions remain open. In this respect, Canadian literature written by Italian writers is a textbook case: a metaphor for our universe in perpetual transformation.

At the end of this dense and all-too-brief panorama, it’s timely to ask whether Italian-Canadian literature is the product of ultraliberal consumerism, or the culmination of emancipation assumed by a mature immigrant community ? Ottawa academics William Anselmi and Kosta Gouliamos argue for the first side of the equation in Elusive Margin – Guernica 1998 – , while Franco Loriggio explores the second in the essay he once edited: Social pluralism and Literary History – Guernica 1996. In this period of identity withdrawal, will his fertile exchange with Italian-Canadian literature endure? These questions remain open. In this respect, Canadian literature written by Italian writers is a textbook case: a metaphor for our universe in perpetual transformation.

___________________________________________________________________________

i Colonial libraries, whether private or religious, already had a few thousand books in Italian. On this subject, read Amelie Ferrigno’s article ‘Italian books in Montreal collections’ https://journals.openedition.org/diasporas/4994

ii The historian Robert H. Harney, specialist in Italian immigration to America, used the term ‘the final frontier’ to describe the movement of mass Italian immigration from South America north to Canada in the middle of the 19th century.

iii Early publications included L’Italo-Canadese, founded in 1893, Il corriere del Canada, 1895, La Patria Italiana, 1904, followed in the 1930s by the weekly Il Citttadino canadese, 1941, and in later decades by Corriere canadese, Il corriere Italiano, 1952–2023, and Tribuna Italiana, 1963.

iv Italian writers should practice it systematically, see: Self-translation as a problem for Italian-Canadian writers Joseph Pivato*géfile:///C:/Users/Fulvio%20Caccia/Downloads/936-1864-1-SM.pdf

v Duliani’s career deserves a closer look. This Istrian-born critic and playwright wrote in both French and Italian. His plays were performed in France and Canada, and one of them, La fortune vient en parlant, was even introduced by Edit Piaf in 1949.

vi The French daily newspaper Le Monde devoted a full page of its pages to him.

vii On this subject, see Le projet transculturel de ‘ViceVersa’, proceedings of the international seminar of the CISQ in Rome, edited by Anna Mossetti, Rome, 2006, 117 pages.

viii Named after the Italian Jesuit who became one of the famous ‘Canadian Martyrs’. This prize is awarded to an Italian-Canadian writer, depending on the literary genre.